Researchers in India and Japan have developed an improved method for using graphene-based transistors to detect disease-causing genes.

The team improved sensors that can detect genes through DNA hybridization, which occurs when a 'probe DNA' combines with its complementary 'target DNA.' Electrical conduction changes in the transistor when hybridization occurs. The improvement was done by attaching the probe DNA to the transistor through a drying process. This eliminated the need for a costly and time-consuming addition of 'linker' nucleotide sequences, which have been commonly used to attach probes to transistors.

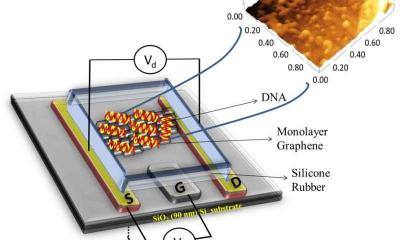

The research team designed GFETs that consist of titanium-gold electrodes on graphene deposited on a silicon substrate. Then they deposited the DNA probe, in a saline solution, onto the GFET and left it to dry. They found that this drying process led to direct immobilization of the probe DNA on the graphene surface without a need for linkers. The target DNA, also in saline solution, was then added to the transistor and incubated for four hours for hybridization to occur.

The GFET reportedly operated successfully using this preparation method. A change in electrical conduction was detected when the probe and target combined, signaling the presence of a harmful target gene. Conduction did not change when other non-complementary DNA was applied.

DNA hybridization is usually detected by labeling the target with a fluorescent dye, which shines brightly when it combines with its probe. But this method involves a complicated labeling procedure and requires an expensive laser scanner to detect fluorescence intensity. GFETs could become a cheaper, easier to operate, and more sensitive alternative for detecting genetic diseases.

"Further development of this GFET device could be explored with enhanced performance for future biosensor applications, particularly in the detection of genetic diseases," conclude the researchers in their study.