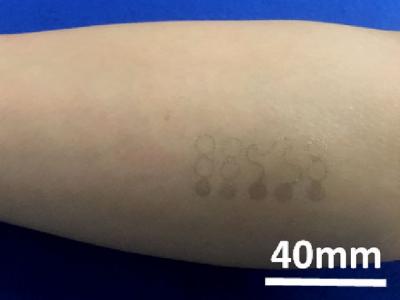

Researchers at the University of Texas have developed a graphene-based health sensor that attaches to the skin like a temporary tattoo and takes measurements with the same precision as bulky medical equipment. The graphene tattoos are said to be the thinnest epidermal electronics ever made. They can measure electrical signals from the heart, muscles, and brain, as well as skin temperature and hydration.

The research team hopes to integrate these sensors applications like consumer cosmetics, in addition to providing a more convenient replacement for existing medical equipment. The sensor takes advantage of graphene's mechanical invisibility - when the sensor goes on the skin, it doesn’t just stay flatâit conforms to the microscale ridges and roughness of the epidermis.

The Texas researchers started by growing single-layer graphene on a sheet of copper. The 2D carbon sheet is then coated with a stretchy support polymer, and the copper is etched off. Next, the polymer-graphene sheet is placed on temporary tattoo paper, the graphene is carved to make electrodes with stretchy spiral-shaped connections between them, and the excess graphene is removed. Then the sensor is ready to be applied by placing it on the skin and wetting the back of the paper.

In their proof-of-concept work, the researchers used the graphene tattoos to take five kinds of measurements, and compared the data with results from conventional sensors. The graphene electrodes were able to pick up changes in electrical resistance caused by electrical activity in the tissue underneath. When worn on the chest, the graphene sensor detected faint fluctuations that were not visible on an EKG taken by an adjacent, conventional electrode. The sensor readouts for electroencephalography (EEG) and electromyography (EMG, which can be used to register electrical signals from muscles and is being incorporated into next-generation prosthetic arms and legs) were also of good quality. The sensors could also measure skin temperature and hydration, which could be useful for cosmetics companies.

Graphene’s conformity to the skin might be what enables the high-quality measurements. Air gaps between the skin and the relatively large, rigid electrodes used in conventional medical devices degrade these instruments’ signal quality. Newer sensors that stick to the skin and stretch and wrinkle with it have fewer airgaps, but because they’re still a few micrometers thick, and use gold electrodes hundreds of nanometers thick, they can lose contact with the skin when it wrinkles. The graphene in the Texas researchers’ device is 0.3-nm thick. Most of the tattoo’s bulk comes from the 463-nm-thick polymer support.

The next step is to add an antenna to the design so that signals can be transmitted from the device to a phone or computer.