A team of researchers at the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) in Korea have measured and controlled the temperature of individual graphene bubbles with a single laser beam for the first time.

They explain that the highly elastic and flexible nature of graphene allows for the creation of stable large bubbles, in a relatively controlled fashion. The strain and curvature introduced by the bubbles is known to tune the electronic, chemical, and mechanical properties of this material. Generally, graphene bubbles are more reactive than flat graphene, so they might be more easily decorated with chemical groups. Bubbles might serve as tiny, closed reactors, and their curved surface could provide a lens effect. Understanding how temperature varies within bubbles is an important factor for several applications.

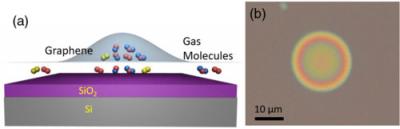

In this study, bubbles are formed at the interface between a graphene sheet and a silica (SiO2/Si) substrate it lies on. The SiO2 surface attracts some molecules that evaporate when heated, creating bubbles.

As also predicted by the theorists of the team, the temperature oscillates with the bubble height. Although each bubble is only several micrometers in width and about one micrometer in height, the scientists could detect a variation in temperature, not only between the center and the edges, but also at different heights of the bubble.

When a graphene bubble is illuminated with a laser beam, incident and reflected rays overlap forming an optical standing wave on the surface. Increasing the laser power has the effect of selectively heating specific regions of the bubble, which correspond to the maximum interference of the standing optical wave. IBS scientists detected local changes in temperature within each bubble using Raman spectroscopy.

"Standing waves near surfaces have been ignored for a long time and have only rarely been observed in a direct manner. The results are surprising. The laser beam can efficiently heat the graphene, and we can determine the thermal conductivity in graphene bubbles from its temperature distribution," explains Wolfgang Bacsa, one of the members of the team, and visiting scientist from CEMES-CNRS and University of Toulouse in France.

"These results confirm the high thermal conductivity of graphene previously measured, demonstrate the excellent adhesion around the perimeter of the graphene bubble, and provide new perspectives on how to heat graphene bubbles on specific locations," concludes Rod Ruoff, coauthor and director of the Center for Multidimensional Carbon Materials. "The more we know about the physical properties of graphene bubbles, the more we might be able to make use of them in different ways."

A promising application could be the creation of graphene sheets with circular holes, like a 'polka dot' pattern. As overheating of the bubbles causes them to burst, the pores decorated with specific chemical groups could work as molecular selective filters.